Search articles

Disaster Governance: Powered by Prayers, Memes, and Ayuda Raffles

Why disaster laws keep failing, rescuers keep dying, and we keep laughing through the pain of loss.

Alas, we have come to July, Disaster Resilience Awareness Month. Timely, the rain pours, the government suspends class and work, and memes come flooding in. This is the time of the year when “we tell ourselves that the Filipino spirit is waterproof.”

Never mind the knee-deep water in classrooms. Never mind the stranded commuters posting for help on the expressway. Never mind the minimum wage earners braving the storm like superheroes, if only to get his or her fair wage for the day. We smile through storms. We have resilience.

But somewhere beyond the memes and the soaked relief goods, we need to ask: are we celebrating our strength as a nation, or have we grown so accustomed to calamities that we've lost hope for improved disaster response?

The Law Says We Should Be Ready, So Why Aren’t We?

While the whole of Luzon was drenched by three typhoons, I delivered an online lecture for the Visayas group on Human Rights Based Approach. As I often remind my students and colleagues, our laws reflect a vision of resilience rooted in duty, rights, and equity – not charity.

Let’s not pretend we’re without legal muscle. Several laws institutionalize disaster prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery, especially for the vulnerable groups.

RA 10121 (Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2010)

This landmark law shifted the country’s disaster approach from reactive (disaster response) to proactive (risk reduction and preparedness).

In a nutshell, RA 10121 institutionalizes the Four Pillars of DRRM and organizes disaster work into four thematic areas:

Disaster Prevention and Mitigation

- Structural: flood control, early warning systems, hazard mapping

- Non-structural: land use planning, reforestation, climate resilience

Disaster Preparedness

- Community drills, education campaigns, early warning systems, pre-disaster logistics

Disaster Response

- Evacuation, rescue, relief operations, emergency health and shelter services

Disaster Rehabilitation and Recovery *

- Post-disaster needs assessment (PDNA), rebuilding infrastructure, psychosocial support

Key players in DRRM are:

National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) as the lead policy-making and coordination body. It is composed of key agencies like the DILG, DSWD, DOH, DepEd, and AFP to name a few. The Office of Civil Defense (OCD) functions as secretariat and operational arm.

Local DRRM Councils (LDRRMCs) mirror the NDRMMC as lead policy-making and coordination body in barangay, municipal, city and provincial levels, while Local DRRM Offices serve as operational arms of local councils.

Under Section 21 of RA 10121, each LGU must allocate not less than 5% of of the estimated revenue from regular sources to the Local DRRM Fund for to support disaster risk management activities such as, but not limited to, pre-disaster preparedness programs including training, purchasing life-saving rescue equipment, supplies and medicines, for post-disaster activities, and for the payment of premiums on calamity insurance. Of the amount appropriated for LDRRMF, thirty percent (30%) shall be allocated as Quick Response Fund (QRF) or stand-by fund for relief and recovery programs in order that situation and living conditions of people In communities or areas stricken by disasters, calamities, epidemics, or complex emergencies, may be normalized as quickly as possible.

RA 10821 (Children’s Emergency Relief and Protection Act)

This law aims to ensure comprehensive protection for children before, during, and after disasters and emergencies, specifically by mandating the:

Establishment of child‑friendly safe spaces and evacuation centers that prioritize privacy, sanitary facilities, and maternal‑infant care

Provision of transitional shelters for orphaned or unaccompanied children, pregnant and lactating mothers with gender-specific and child-sensitive facilities

Immediate delivery of basic needs—food, water, medicine, hygiene kits—prioritizing children under 5, pregnant women, and PWDs

Enforcement of safety measures coordinated by PNP, AFP, DSWD, DILG, DepEd, and CSOs specifically targeting child exploitation, trafficking, abuse, and neglect

Provision of health and psychosocial services provided in coordination with DOH, LGUs, and NGOs

Rapid resumption of education, including early learning services, in coordination with DepEd and other agencies

Family tracing and reunification protocols for orphaned/separated children

Systems to restore lost civil registry documents and register children born during emergencies

Mandatory training for responders on child protection and psychosocial care

Age‑, gender‑, and ability‑disaggregated data collection in DRRM systems to understand and respond better to the needs of children affected by disasters and calamities

Listo si KAP

The DILG launched "Listo si KAP" (Komunidad at Punong Barangays), a disaster preparedness and response framework for barangays, aligning with President Marcos Jr.'s call for safer communities. Building on "Operation L!sto," this initiative provides protocols for pre-disaster vigilance, imminent hazard actions, and post-disaster needs assessments. Memorandum Circular No. 2025-035 designates the Barangay Development Council as the Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (LDRRM) Council, approving plans and recommending emergency measures like preemptive evacuation. The Barangay DRRM Committee (BDRRMC) acts as the LDRRM Office, crafting and executing disaster risk management programs. BDRRMC responsibilities include drills, equipment readiness, and infrastructure audits during preparedness; activating operations centers, managing evacuation, and coordinating search and rescue during response; and post-disaster damage assessment, rehabilitation, and sustainable recovery solutions. Listo si KAP reinforces the DILG's commitment to empowering barangays for disaster resilience.

LGU Resilience Readiness Monitoring Framework (LRRMF)

The Local Resilience Readiness Measurement Framework (LRRMF) under DILG Memorandum Circular No. 2020-043 covers:

Disruption (Hazard and Exposure): This describes the intensity of natural hazards (e.g., earthquakes, typhoons, landslides, floods) and exposed assets that challenge an LGU's protective capabilities. Disruptions are classified as potential (estimated hazard intensities) and actual (recorded effects of recent disasters). This component profiles the LGU's hazards and exposed elements, assessing risk management effectiveness.

Contextual Vulnerability: These are pre-existing LGU factors (economic, social, environmental, institutional conditions) that influence initial resilience and susceptibility to hazards, either aiding or hindering risk reduction efforts.

Risk Governance (Capacity): This refers to the systems, institutions, policies, and leadership within an LGU that guide disaster risk reduction, climate change, and development efforts. It encompasses technical and functional capabilities in areas like organizational functionality, risk information, safe environments, emergency response, and resilient critical services.

Allocation and Utilization of the Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Fund (LDRRMF)

Joint Memorandum Circular No. 2013-1 provides guidance to Local Government Units (LGUs) on the allocation and utilization of the Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Fund (LDRRMF). Its primary objectives are to ensure efficient and effective use of these funds and to promote transparency and accountability in their management.

Despite the presence of detailed laws and institutional structures, disaster risk reduction in the Philippines remains largely ineffective because those in power often treat it as a procedural requirement rather than a moral responsibility. As Panao argues, the system suffers from a lack of political accountability and sustained leadership, leading to a cycle of reactive aid and post-disaster blame rather than proactive, risk-informed governance.

Recently, the Commission on Audit (COA) regularly flags LGUs for unspent or mismanaged DRRM funds, with some barely using their Quick Response Fund and mitigation budget. In Batangas Province alone, auditors flagged ₱23 million unutilized disaster funds (45.85% non-utilization rate) as of 2023, while many municipalities still have unliquidated balances improperly parked instead of being invested in resilience.

According to a 2024 Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI) study, Filipino persons with disabilities (PWDs) experience significantly higher barriers in disaster preparedness and recovery—due to inaccessible infrastructure, lack of inclusive communication, and weak local enforcement of RA 10754. The study noted that many Local Government Units (LGUs) lack PWD directories, hindering pre-disaster planning; evacuation centers often lack accessible features; PWDs report exclusion from disaster drills and information; and only 20% are aware of their rights under RA 10754.

Last Monday, extreme flooding along critical stretches of the North Luzon Expressway (NLEX)—notably in Balintawak and Valenzuela—left thousands of motorists stranded for hours after rain-swollen creeks and malfunctioning pumps overwhelmed infrastructure. In response, the Department of Transportation (DOTr) and the Toll Regulatory Board (TRB) issued a show-cause order to NLEX Corporation, demanding an explanation for the failure despite warnings issued in May, months before the rainy season kicked in.

“Resilience isn’t about laughing through it—it’s about not having to survive this way again.”

Typhoons have long been part of our lives, woven into the rhythms of our rainy seasons and family emergency plans. Over time, we’ve learned to meet these storms with equal parts preparation and humor. But sometimes, that humor seeps into places where urgency should lead. On official social media pages, even class suspension announcements come with jokes and trending memes—well-meaning perhaps, but occasionally blurring the line between public service and entertainment. In one town in Central Luzon, an e-ayuda distribution was turned into a digital raffle, where residents submitted photos of themselves in flooded homes to qualify. It speaks to how deeply we rely on creative coping—and how, maybe, we’re still figuring out how to match empathy with efficiency in times of crisis.

Typhoons are part of life here—we brace, we survive, and often, we laugh. But lately, the gravity of disaster has been reduced to jokes and memes. Class suspensions come with punchlines. In one town, e-ayuda became a raffle where people had to pose in floodwaters.

But there’s nothing funny about long-term loss. These may seem lighthearted on the surface—but behind every soaked selfie is a family facing loss: damaged homes, weeks of lost income, children missing school, and a recovery process that can stretch for years. Resilience isn’t about laughing through it—it’s about not having to survive this way again.

In Case You Missed It: Even Our Rescuers Aren’t Safe

Let’s rewind to 2022, the onslaught of Typhoon Karding left five season rescuers dead during a mission in San Miguel, Bulacan. They launched a boat to save others, but a concrete wall collapsed on them. Not because they were reckless. But because infrastructure failed, and protocols weren’t enough to protect them.

“Disasters don’t just kill victims. They also claim those trying to help—when systems treat resilience like a virtue instead of a duty.”

Then just days ago, in Meycauayan City, a barangay health worker was electrocuted in a flooded area near the Barangay Health Station. She was on her way to check the safety of medical supplies. A wire had come loose above a tent she passed through.Just days ago, tragedy struck Meycauayan City when a barangay health worker, en route to check on the safety of vital medical supplies, was electrocuted in a flooded area near the Barangay Health Station. A loose wire, dangling ominously above a tent she passed through took her life.

That’s the thing: disasters don’t just kill victims. They also claim those trying to help—when systems treat resilience like a virtue instead of a duty.

Small Steps, Big Leaps

If we want fewer dead rescuers, fewer TikToks of people on rooftops, fewer public apologies—we might consider the following:

✅ Protect the Protectors

Give rescuers and health workers real hazard training, not just jackets and hashtags.

Assess their stations.

Audit their gear.

And for once, ask them what they need before a storm—not after the eulogy.

✅ Map Relationships, Not Just Names

Disasters don’t care about your census forms. They care if no one knows that Lola Pilar lives alone two streets down and hasn’t been able to walk since January.

You know what else we track? Not just names, but who lives alone. Who’s on maintenance meds. Who needs someone to remind them that yes, the typhoon’s real, and no, it’s not just “ulan lang 'yan.”

✅ Practice Quiet Readiness

Skip the motorcade.

Start with radios that work.

Barangay-level (you can go granular as Puroks or Sitios) simulations in alleyways, not auditoriums.

Train community leaders with no rank but real trust: vendors, jeepney barkers.

Flood maps that are in the local language.

And policies that don’t get activated only when it’s too late.

Emergency kits in sari-sari stores and each households.

✅ Track Dignity, Not Just Damage

Ask survivors if they were treated like human beings, or like statistics with feet. Did families stay together? Were the elderly given mats or left on the floor? Did evacuees feel safe—or forgotten?

✅ Stop Treating Accountability Like an Afterthought

If an expressway floods, someone signed off on the drainage. If people die in shelters, someone designed those buildings. If funds were allocated, show the receipts—and the outcomes.

Redefining Resilience

So here we are. Another July. As I write, lightning flashed and painted the night sky. Thunders roared. Rain lashed, wind howled. I know it's going to be a long night, decisions have to be made. Relief efforts need to mobilize.

As I scan social media, resiliency remains to be a buzzword.

Nostalgia hits. It was 2005. A typhoon had just passed, and I joined a high school writing competition. The prompt was simple: What can we learn from the typhoon? I wrote about resilience—how we rise, rebuild, and help one another through the storm. That piece won me the top prize and qualified me for the National Schools Press Conference. At sixteen, I believed that was what resilience meant.

Now, nearly two decades later, I still believe in resilience—but not in the way I once did. Resilience must go beyond enduring floods and laughing through crisis. It must mean refusing to normalize preventable suffering. It must mean accountability, preparedness, and a system that works before the next storm hits—not just after.

Real disaster governance doesn’t just come from the government. It comes from everyone: the head of a family voluntarily evacuating from high-risk areas; a student who brings emergency kits; a mother who keeps herself update with weather reports; the school teacher who checks on his or her students and their families; tricycle driver who knows who lives on the lowest street; and nurse who deserves to return home after a shift—alive, and dry.

This Disaster Resilience Month, let’s stop romanticizing recovery. Let’s start demanding readiness. And maybe, just maybe—fewer funerals for those who tried to save us. If you ever post #ResilientFilipino again, make sure it’s not because the system failed—but because we made it work.

“Resilience must go beyond enduring floods and laughing through crisis. It must mean refusing to normalize preventable suffering. It must mean accountability, preparedness, and a system that works before the next storm hits—not just after.”

Injured, Silenced, Denied: The Real Cost of Medical Negligence

A child dies after a routine circumcision. A nurse pleads for PPE and dies alone. A mayor recovers from COVID—only to contract a fatal infection in the ICU. Each of these stories ends in mourning. But few end in court.

In country of more than 118 million people, where medical decisions are made daily across thousands of clinics, hospitals, and birthing centers, the Philippine Supreme Court has decided only 28 cases that mention either “medical negligence”or “medical malpractice” from 1990 to 2025.

Fewer than 50 cases in 35 years. This isn’t a sign of perfection. It’s a sign of silence.

What we see on record is a trickle. The rest stays unspoken.

This is not a system that encourages justice. It is a system that quietly, persistently shuts the door.

Cases Die Without Experts

In Philippine courtrooms, medical negligence cases rarely survive without the testimony of a physician from the same field as the accused. Without that expert, the case often dies on arrival—unless the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur clearly applies.

No expert, no case. Even when complainants present witnesses, the testimony must come from someone credentialed in the field directly related to the alleged act of negligence.

In Que v. Philippine Heart Center (2025), the Supreme Court made this threshold even more explicit:

“As a forensic pathologist, Dr. Fortun cannot qualify as an expert witness in so far as to determine whether Dr. Aventura exercised the norm observed by other reasonably competent members of the profession.”

In Borromeo v. Family Care Hospital (2016), the Court rejected testimony from a general practitioner and a legal expert in medical jurisprudence:

“Dr. Reyes is not an expert witness who could prove Dr. Inso’s alleged negligence… His testimony cannot be relied upon to determine if Dr. Inso committed errors during the operation.”

“Dr. Avila… testified in his capacity as an expert in medical jurisprudence, not as an expert in medicine, surgery, or pathology. His testimony fails to shed any light on the actual cause of Lilian’s death.”

Instead, the Court gave greater weight to the defense’s experts—Dr. Ramos, a board-certified pathologist, and Dr. Hernandez, a seasoned general surgeon:

“To our mind, the testimonies of expert witnesses Dr. Hernandez and Dr. Ramos carry far greater weight… The petitioner’s failure to present expert witnesses resulted in his failure to prove the respondents’ negligence.”

In theory, this evidentiary rule filters out unreliable testimony. In practice, it narrows the gate so tightly that many valid claims are shut out. Across jurisdictions, legal scholars and medical commentators have noted how few specialists are willing to testify against their peers. The reasons range from professional loyalty to reputational risk. This dynamic is often referred to as the “conspiracy of silence” within the medical profession (Okoli, 2019; Wood, 1986). The result? Legitimate complaints wither for lack of qualified expert witnesses.

Technical Barriers to Justice

The law gives patients four years to file a malpractice complaint. That clock starts ticking from the time the cause of action accrues—often interpreted as the time of injury, not necessarily the time the patient understands what went wrong.

In De Jesus v. Uyloan (2022), the Supreme Court dismissed a gallbladder surgery case—not because negligence was disproven, but because it was filed outside the prescriptive period. The patient underwent a corrective surgery two months after the first procedure, yet the complaint was filed nearly five years later.

The reasons for delayed filing? We can only guess. The case was silent.

This silence is deafening. It hints at something more complex—perhaps emotional exhaustion, financial paralysis, or simply confusion. Perhaps the patient wasn’t sure she had a case. Perhaps she hoped the second surgery had fixed what went wrong. Perhaps she was afraid to confront the system that failed her.

Some researchers suggest that psychological trauma, avoidance behaviors, or loss of trust in the system can delay patients from confronting malpractice. But more empirical studies are needed to understand these patterns fully. In the Uyloan case, there was no indication as to why the delay occurred.

Adding to this fog is a legal ambiguity rarely acknowledged outside courtrooms: was the claim one of breach of contract or of quasi-delict? The prescriptive periods differ—six years for the former, four for the latter. In Uyloan, this lack of clarity may have further delayed the decision to file. The very act of choosing the legal theory becomes a strategic gamble—and for many, a trapdoor.

These are the technical barriers to justice. A procedural rule meant to protect against stale claims becomes, in effect, a barricade. And patients, already reeling, are forced to navigate a legal minefield without a map.

The Cost of Filing a Case Is Higher Than Most Can Afford

Pursuing a malpractice claim isn’t just about courage—it’s about capacity. Filing fees. Expert opinions. Lawyer’s fees. Court appearances. These costs accumulate long before a judge hears the case.

Years ago, I assisted a client in a physical injury case. We sought a medico-legal expert. She was reputable and upfront:

“I charge ₱5,000 per court appearance.”

Now imagine a malpractice case that spans years, with multiple hearings and possible appeals. Even a conservative estimate balloons into a financial burden, especially for families already reeling from hospital bills and lost wages.

In another experience involving a case of psychological incapacity, one expert charged ₱100,000 as an acceptance fee, which included the preparation of the report. Another charged ₱30,000 per appearance in court. When these figures were laid out, clients balked. One even considered withdrawing the case.

This isn’t meant to disparage expert witnesses—their time, expertise, and credibility matter. But it’s a stark reality: many middle-income Filipinos simply can’t afford the price tag attached to justice. And if middle-income Filipinos struggle to afford these fees, how much more for the poor?

When Faith Replaces Fight

In many Filipino households, when tragedy strikes, the response isn’t legal—it’s spiritual.

Kalooban ng Diyos. God’s will. A phrase whispered over hospital beds, funeral parlors, and even courtroom steps. It offers comfort, yes—but it can also cloud accountability.

The idea that suffering has divine purpose is deeply rooted in Filipino culture. When a medical procedure goes wrong, many families are more likely to pray than to pursue. They focus on healing or mourning—not hiring a lawyer.

This fatalism, while rooted in resilience, can delay or derail a family’s pursuit of justice. There is often a quiet, unspoken belief that suing a doctor—even a negligent one—is wrong. Some see it as karma, others as pasalamat na lang buhay pa(“at least they survived”), and still others as too much emotional energy in a system they don’t trust to begin with.

Legal remedies are viewed not just as inaccessible—but inappropriate. Especially in the provinces, community ties with local doctors, small-town dynamics, and respect for authority figures mean that filing a case is not only a legal act—it’s a social rupture.

This is not to say that Filipinos do not care about justice. But many believe that justice, like healing, should be left to God.

The result? Valid complaints are never filed. Not because they lack merit, but because they’re buried under silence, fear, and faith.

When They Don’t Know What To Do

Sometimes, people simply don’t know where to begin. I once received a message from a friend, a nurse, who confided her deep regret after her mother passed away following surgery. She had a gut feeling something went wrong, but she didn’t know how—or whether—to act. That hesitation never left her.

This is another silent barrier: uncertainty. The legal system is foreign to many, especially in times of grief. They don’t know what documents to gather, whom to consult, or what steps to take. Inaction is not apathy. It’s paralysis.

In a country where health literacy and legal literacy do not always intersect, even educated professionals can feel lost. And so another valid case quietly disappears—not for lack of cause, but for lack of compass.

In contrast, in Ramos v. Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court upheld the testimony of a nurse who was a relative of the patient as valid, relying on the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur:

“Testimony as to the statements and acts of physicians and surgeons, external appearances, and manifest conditions which are observable by anyone may be given by non-expert witnesses.” — Ramos v. Court of Appeals, Delos Santos Medical Center, et al., G.R. No. 124354, December 29, 1999.

The Court also documented her observations:

“At about 12:15 P.M., Herminda Cruz, who was inside the operating room with the patient… heard Dr. Gutierrez say, ‘ang hirap ma-intubate nito, mali yata ang pagkakapasok. O lumalaki ang tiyan.’… She thereafter noticed bluish discoloration of the nailbeds of the left hand… [which] is an indication that there is a decrease of blood supply to the patient’s brain.”

The ruling shows that courage to step forward and assert one’s observations can sometimes break through the barriers. Patients and families must be empowered to ask the right questions—and the right people.

Silence in the System: Settlements and Non-Disclosure

Sometimes, cases don’t reach court—not because the harm was minor, but because the settlement was enough. Hospitals and doctors may offer financial settlements early in the process, sometimes before a formal complaint is filed. In other cases, a family may agree to stop pursuing the case in exchange for a lump sum or written apology.

But not all settlements are signs of closure. They may reflect exhaustion, intimidation, or sheer economic necessity. For many families, the weight of daily survival is heavier than the weight of pursuing justice.

Settlements can bring relief. But they also reinforce a culture of non-accountability. When complaints are withdrawn, patterns of neglect can remain hidden.

The Burden of Trauma and Double Victimization

For victims of medical harm, coming forward means reliving the worst chapter of their lives. Legal processes require statements, affidavits, cross-examinations—each one a re-opening of wounds.

Some patients, already grieving, fear the emotional toll of litigation. They worry they won’t be believed, that their grief will be dissected in court, or that they’ll be blamed for not speaking up sooner.

This is what experts call “double victimization” — first at the hands of the negligent act, and then again through the adversarial legal system. When the process feels punishing rather than protective, silence becomes safer.

Lack of Awareness and Legal Literacy

Many Filipinos simply don’t know that malpractice is actionable. Others know—but don’t know how. The medical field is technical; the legal field, no less so. When these two systems collide, ordinary patients feel out of place.

There is little public education around medical rights. Few hospitals display information on how to file a complaint or what red flags to watch for. This vacuum of knowledge keeps people passive.

Justice is a right—but it’s not common knowledge. Until that changes, many wrongs will remain untouched. Especially among Filipinos, who are non-litigious by nature.

Conclusion: When Knowledge Becomes Power

Medical harm doesn’t always leave bruises. Sometimes, it leaves questions—unanswered, unheard, unfiled.

In the Philippines, the greatest barrier to accountability isn’t just the law or the cost. It’s the quiet. The hush after the surgery. The whispered regrets. The absence of names in court records. Justice, it turns out, is not just a right—it’s a language. And too few are taught to speak it.

Until we give ordinary patients the tools to ask, to understand, and to act, medical negligence will remain a wound that festers in silence.

If this blog made you pause, or think of a story untold, maybe that’s where it starts: not with a lawsuit, but with knowing you could.

Read. Reflect. Speak.

Because knowledge isn’t just power—it’s protection.

Fraud, Silence, and Stereotypes: Rethinking Roldan Through a Gender Lens

A pile of magazines—photographs of half-naked men—sparked a confession. The husband came out years into the marriage. The wife sued for annulment based on fraudulent concealment of homosexuality, a ground recognized under Article 45(3) in relation to Article 46(4) of the Family Code.

The Supreme Court annulled the marriage. This decision, on its face, adheres to legal doctrine. But as a law professor who teaches Gender Sensitivity and the Laws on Women and Children, I find it necessary—both as a teacher and as a citizen—to reflect on the reasoning that underpins the Court’s conclusion. This is not an indictment of the judiciary, but a teaching moment.

In particular, one line in the ruling deserves closer attention:

“No woman would put herself in a shameful position if the fact that she married a homosexual was not true. More so, no man would keep silent when his sexuality is being questioned thus creating disgrace in his name.”

This language—though perhaps intended to emphasize sincerity—draws from a pool of gendered assumptions. It invites us to ask: what kind of masculinity does our law expect? And when a man is silent, does that automatically mean he is guilty of deception?

Though laws evolve and rights expand, the institution of marriage remains entangled in the quiet grip of patriarchy. Unmasking it means asking who benefits from the silence—where equality is promised, but tradition still tips the scale.

The Law on Fraudulent Concealment

In Almerol v. RTC (G.R. No. 179620, October 5, 2010), the Supreme Court was unequivocal:

“Consent is an essential requisite of a valid marriage. To be valid, it must be freely given by both parties. An allegation of vitiated consent must be proven by preponderance of evidence.”

The Family Code provides a closed list of fraudulent acts that may vitiate consent. Homosexuality per se is not a ground for annulment—it is the fraudulent concealment of it prior to the marriage that is actionable. Thus, concealment is not merely silence—it must be deliberate misrepresentation. It is this subtle but crucial threshold that jurisprudence demands.

“Concealment...is not simply a blanket denial, but one that is constitutive of fraud.”

When Distance Doesn’t Mean Deceit

Recalling Almerol's vital reminder that fraud requires not only omission, but bad faith.

Let’s return to Roldan. The facts noted by the Court include:

Lory, on their first date, did not sit beside Jaaziel or hold her hand.

He said he was shy.

He admitted Jaaziel was his first girlfriend.

Her father found him "not man enough," and said he was "malambot."

Do these facts alone amount to fraudulent concealment? Awkwardness. Introversion. Social inexperience. Effeminacy. None of these are inherently deceptive. They may be atypical—even disappointing—in a romantic partner, but to interpret them as proof of fraudulent concealment treads dangerously close to gender stereotyping.

Fraud, in law, is not about failing to meet gender norms. It is about willfully hiding a material fact with intent to deceive. And even if Lory was unsure or questioning his identity, is uncertainty equivalent to dishonesty?

The danger in Roldan is that the Court appeared to conflate gender nonconformity with concealment, and silence with deception. As educators, we must interrogate this logic.

Reading of Roldan Through Feminist Legal Method

I recall a class with Justice Alicia Sempio-Diy, one of the drafters of the Family Code, at the peak of the drama series My Husband's Lover. She found it fascinating to discuss the topic in class, particularly how the law views identity, love, and deception within marriage. Years later, Roldan v. Roldan presents a real-life case to revisit these questions— not as mere entertainment, but as constitutional, cultural, and human issues. The Strategic Plan for Judicial Innovations (SPJI) promotes legal feminism through three guiding methodologies. Let us revisit Roldan through that lens:

1. Unmasking Patriarchy

The Court’s language implies that being married to a gay man is shameful. But dignity is not erased by sexual orientation. Shame arises not from queerness — but from a culture that sees queerness as a flaw. The law must not validate pain rooted in patriarchy without first interrogating the source of that pain.

2. Contextual Reasoning

The Court viewed the lack of affection and distance as proof of fraud. But awkwardness, inexperience, and emotional unavailability are not always signs of concealment. Especially if, as the wife admitted, this was his first relationship.

3. Consciousness Raising

The husband’s silence was interpreted as guilt. Yet silence is not always strategic. Sometimes it is born from trauma, confusion, or internal conflict. In a society that punishes queerness, coming out is not always safe, linear, or possible. Legal feminism teaches us to see the interiority behind silence.

Fraud must be proven, not presumed. And gendered behavior must not become evidence of duplicity by default.

This case invites a deeper discourse on queer identity and marriage as a social institution. It demands more from us—to think critically, judge compassionately, and teach courageously.

What the Law Must Learn and Unlearn

This case leaves us with a question: Are we holding people liable for who they are — or for what we fear they might be?

As a professor, I teach that the courtroom is not only a site of justice but a safe space where gender sensitivity could thrive; one that does not discriminate based on gender. What we believe about gender, dignity, and shame is reflected in our rulings. It is also passed on to litigants, students, and the next generation of lawyers and judges.

Is Roldan v. Roldan Aligned with the Supreme Court’s Gender-Sensitive Vision?

Adjudged with the aims of the Strategic Plan for Judicial Innovations (SPJI) —

✅ Where it aligns:

Recognizes fraudulent concealment of homosexuality as a valid legal ground for annulment (under Article 45[3], Family Code).

Upholds that vitiated consent may nullify marriage.

❌ Where it conflicts:

Uses gender-stereotypical language suggesting that homosexuality is shameful or disgraceful.

Interprets effeminacy and shyness as deception, rather than social or personal complexity.

Treats the husband’s silence as proof of guilt, overlooking how queer identities often navigate silence as survival.

🧠 SPJI Goals Potentially Missed:

Unmasking Patriarchy: Instead of questioning the shame narrative, the Court echoed it.

Consciousness Raising: Failed to consider the social risks of coming out.

Contextual Reasoning: Interpreted gender nonconformity as fraud without deeper inquiry into intent.

Let Roldan be more than precedent. Let it spark deeper inquiry. The future of gender-sensitive jurisprudence lies not only in what we decide, but how we reason, and whose truths we allow into the light.

Author’s Note: This commentary is written with profound respect for the Supreme Court. It is offered in the spirit of legal education and feminist scholarship, consistent with the values of transparency, critical inquiry, and transformative justice.

Informed Consent: A Surgeon’s Strongest Legal Tool Against Malpractice

A scalpel might save a life. But a conversation between a doctor and a patient—clear, candid, and properly documented—saves a medical practitioner’s life or career. In the sterile world of operating rooms and legal briefs, few things cut as sharply as informed consent.

It began, as these stories often do, with a consent form and a signature.

A man with an aortic aneurysm was scheduled for a stenting procedure. His surgeon walked him through the risks and his options. He agreed and signed the consent forms. Stenting proved unsuccessful. Days later, he died. The family mourned and, thereafter, lodged a malpractice suit.

This is a short-hand retelling of the case of Que v. Philippine Heart Center, G.R. No. 268308, April 02, 2025. A legal battle that reached its final verdict 25 years after the patient’s death.

The crux of the case lay in a fundamental, but often overlooked, concept in legal medicine: informed consent. In Que, the Philippine Supreme Court reaffirmed one of the most powerful legal doctrines in medicine: informed consent, when rightfully obtained, is sharper than any scalpel.

In a nutshell, the Supreme Court cleared the physician because he fulfilled his duty to explain, inform, and document consent. In the words of the Supreme Court:

“The facts would show that Dr. Aventura informed the Que family, most especially Quintin, of the material risks inherent in the stenting procedure, and that includes death.”

The records show that the patient signed the Consent for Endovascular Stenting and the Consent to Operation, Administration of Anesthesia, and the Rendering of Other Medical Services. His signature appeared in these documents, and this was never questioned.

When tragedy strikes, the conversation between a physician and a patient isn’t just a formality—it becomes evidence, a lifeline in a murky sea of legal scrutiny. The doctrine is not about absolving doctors of blame; it’s about ensuring clarity, mutual understanding, and trust between the caregiver and the cared for.

By no means does the case state that signing a consent is a carte blanche excuse for negligence or malpractice. Malpractice needs to be proven with hard evidence unless it falls under the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur.

Lessons from the courtroom to the operating room

In an overstretched healthcare system, where one physician may be responsible for dozens of patients on any given shift, the ritual of informed consent often collapses into routine. Doctors and nurses, pressed for time, may move robotically through the process: handing over forms that are signed, but not truly understood.

Yes, the paperwork is there. But the information? Often absent.

This is the uneasy paradox at the heart of Philippine hospitals: consent is technically obtained, but substantively hollow. In too many cases, the signature becomes a substitute for the conversation. I have seen this firsthand.

What Que forces us to confront is a powerful truth: informed consent is not merely about protecting the physician or the institution—it’s about empowering the patient. The importance of informed consent resonates as a beacon of communication, one rooted not merely in paperwork but in the human connection that defines caring at its core.

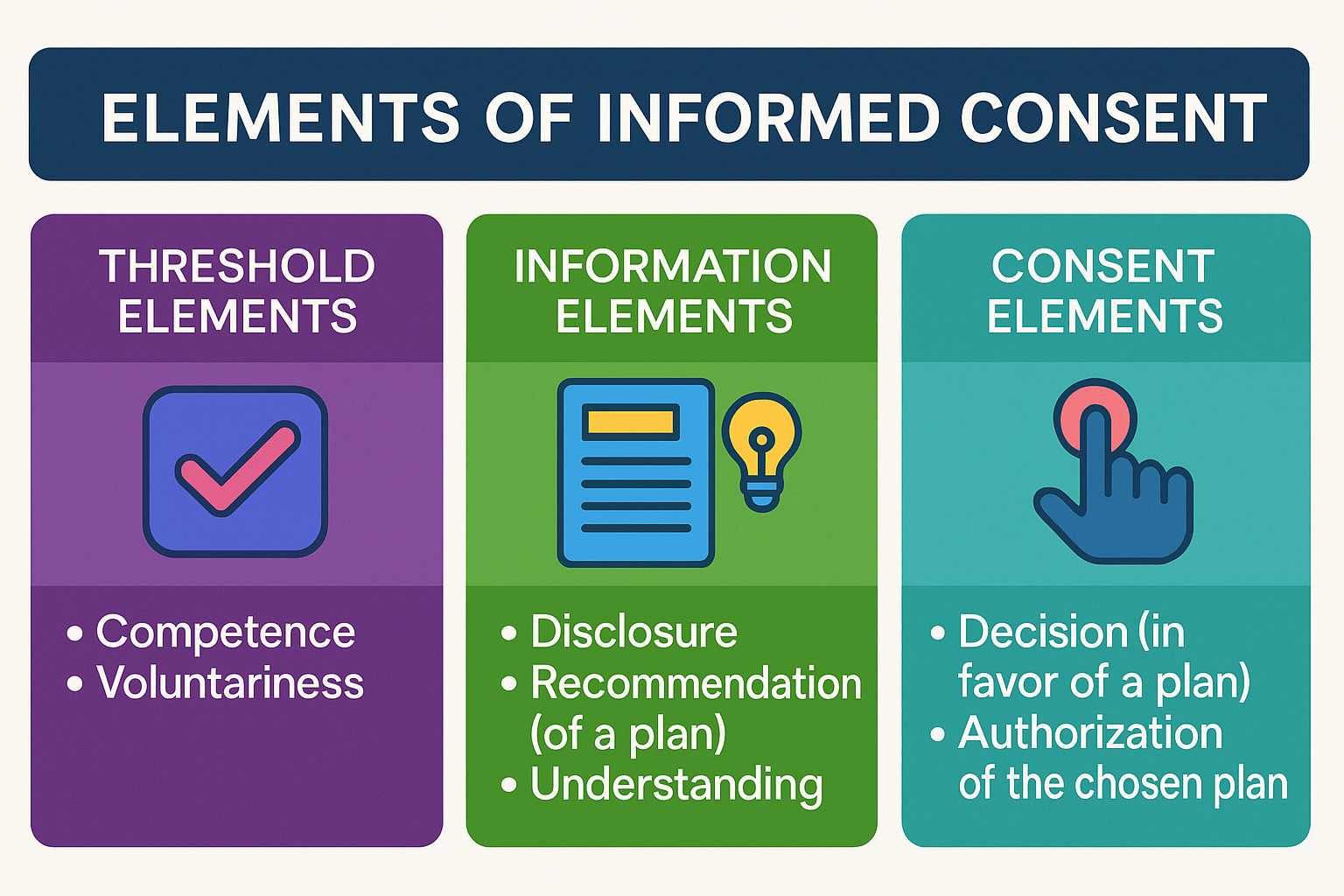

As a lecturer on nursing ethics and legal medicine, I often emphasized a framework first outlined by bioethicists Beauchamp and Childress (2013). This model dissects consent into three pivotal stages: threshold, information, and consent.

This framework is based on the model proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, as cited by the Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University. (Source: Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Meaning and Elements of Informed Consent. Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University. https://bioethics.jhu.edu)

Elements of Informed Consent

Threshold elements serve as the foundational preconditions for informed consent, ensuring that the patient is both capable of making decisions and free from undue influence. A medical practitioner should ascertain the patient’s competence and the voluntariness of decision-making.

Competence refers to the patient’s ability to understand medical information, evaluate options, and make informed decisions. Competence is not merely a legal concept but also a practical one, requiring healthcare providers to evaluate whether the patient has the cognitive and emotional capacity to grasp the implications of their choices.

Voluntariness, on the other hand, underscores the importance of a patient's decision being made free from coercion, manipulation, or external pressures. Whether the influence comes from family members, medical staff, or societal expectations, voluntariness ensures that the patient’s autonomy and personal agency are respected in the decision-making process.

Information elements are crucial to the process of informed consent, ensuring that patients are provided with sufficient details to make a knowledgeable decision regarding their medical care. They include:

Disclosure or the sharing of all material information that a patient needs to understand the medical procedure, including its purpose, benefits, risks, and potential alternatives.

Recommendation that goes a step beyond disclosure by providing the physician's professional opinion on the best course of action. While laying out all the possible scenarios, a healthcare provider must guide the patient toward an informed choice by interpreting the medical data and suggesting a preferred plan.

Understanding -- the final, pivotal component of the information elements– that ensures that the patient not only hears the information but also comprehends it fully. This stage might involve confirming the patient's grasp of the disclosed risks, benefits, and alternatives by engaging them in dialogue, answering their questions, and clarifying any uncertainties. The focus here is to ensure that the patient is genuinely aware and capable of making an informed decision.

Consent elements are essential to completing the process of informed consent and represent the final stage of patient decision-making. They comprise two critical components:

A decision that involves the patient's active choice in favor of a proposed plan or procedure. It is the moment in which the patient exercises their autonomy to determine what they believe to be the best course of action for their health.

Authorization, which marks the formal agreement to proceed with the chosen plan, serves as the confirmation that the patient has willingly provided consent, free from coercion or undue influence. It often involves a signed consent form.

Together, these elements affirm the patient's role as an active participant in their healthcare journey, underscoring the importance of respect, transparency, and ethical practice in medical decision-making.

While the importance of informed consent had been highlighted in earlier precedents, Que serves as a definitive example of the critical importance of informed consent, underscoring its role as a cornerstone of legally sound medical practice.

When tragedy strikes, as it did in this case, consent becomes the anchor that steadies a physician in the storm of loss and litigation, while serving as a testament to the patient’s agency in their own care.

This doctrine, affirmed by the Philippine Supreme Court, should echo in every hospital corridor, every operating room, and every medical school lecture. It demands a rethinking of how we view conversations between doctors and patients—not as perfunctory exchanges, but as critical lifelines, ensuring that medicine remains rooted in the very humanity it seeks to preserve.

No one expects doctors to be insurers of lives. But they are expected to ensure that patients understand the risks in the course of treatment. That means, doctors must exert efforts to:

Speak plainly, not just professionally.

Disclose the full range of risks, including death or disability.

Respect the silence between questions. Listen to what the patient is not saying.

Record the consent not just with ink, but with intention.

The law won’t punish honest medicine. But it does demand transparent communication.

Where is the nurse in all of this?

As a former professor of legal aspects in nursing, I often posed a critical question to my students during case discussions on medical malpractice: where is the nurse in all of this?

It’s a common misconception that nurses secure consent. Legally, that’s the physician’s role. But nurses play a quiet, indispensable one: they advocate. The nursing duty is subtle, but powerful:

Observe whether the patient appears to fully understand the procedure.

Notice verbal and non-verbal cues—hesitation, confusion, fear.

Record any clarifications the patient requests.

Raise concerns to the attending physician before the procedure proceeds.

In healthcare, nurses hold a role less visible but no less vital: ensuring patients are not adrift in uncertainty. While they do not explain the intricacies of medical procedures—that responsibility rests firmly with physicians—they serve as the guardians of comprehension and clarity. Their duty extends beyond care to meticulous documentation, as underscored by the Nursing Code of Ethics for Filipino Nurses: “Accurate documentation of actions and outcomes of delivered care is the hallmark of nursing accountability.” [Article III, Section 6 (3), Board of Nursing Resolution No. 220, s. 2004]. Through this quiet vigilance, nurses stand as the system’s conscience, ensuring every patient’s dignity remains intact.

“Accurate documentation of actions and outcomes of delivered care is the hallmark of nursing accountability.”

What they witness in the hallway or at the bedside may later shape a courtroom’s view of what happened. Nurses aren’t passive bystanders. They are the system’s pulse-check. And when they speak up, they often speak for those who can’t.

Final cut: why consent still matters

Informed consent is not just a line on a checklist. It’s a promise—a small but vital act of dignity in a system that often forgets how human medicine truly is.

When done right, it empowers the patient. It protects the professional. It restores faith in a process that too often collapses into litigation and blame.

The sharpest tool in healthcare isn’t a scalpel. It’s the truth, told clearly, before the first cut.

🙏 Thanks for Reading

If this piece made you pause—or stirred a new question—then it's done its job.

Got something to say? Add your voice below. Got a topic worth unpacking? Tell me.

Subscribe to Seen and Heard for legal insights, reflective storytelling, and honest conversations at the intersection of health and law.

If You’re Crying at 2AM…Burnout, the Bar, and Believing in Yourself

Bar examinees need to breathe too. Every year, thousands of bar examinees walk the tightrope between determination and burnout.

Every year, thousands of bar examinees walk the tightrope between determination and burnout. This piece was born not just from memory, but from a recent conversation — a mentee quietly broke down, and I remembered that night I did too. This isn’t a lecture. It’s a companion. A mirror. A warm hand on the back at 2AM, telling you: you’re not alone.

Anxiety is like a thief that arrives without a warning

I didn’t fret during the review. I was feeling positive about everything. Month after month, I was landing high in the mock bar rankings. On paper, I was peaking. Friends said I looked calm. I believed I was perfectly fine.

Then one night — out of nowhere — it hit me. Like a sweep of sudden dread. An inconsolable feeling of doom. No trigger, no warning. My heart started pounding, my chest tightened, and I couldn’t sleep. Thoughts were racing in my head, a flood of tears suddenly came rushing, and a sense of impending doom overtook my body at 2:00 A.M.

I cried — not because of a codal provision I forgot, but because anxiety arrived like a thief in the night, stealing away my sense of control. And that loss of control? That frightened me more than any question the exam could throw my way.

How did I survive that night? Still, I do not know.

But living to see the light of day the following morning taught me something that codals never did: Bar review isn’t just a test of mastery. It’s a test of self-mastery.

Have you had your 2 A.M. moment yet? The one that makes you doubt everything — even yourself? If you haven’t, it might come.

And if it does, remember this: You’re not breaking down. You’re breaking open.

Maybe you’re counting down too by now. But this is more than a countdown to test day; it’s a rehearsal for something bigger. You memorize the law. You outline jurisprudence. But no one teaches you what to do when anxiety wraps around your chest at midnight and won’t let go. If you’ve ever felt that way — like you’re doing everything right and still falling apart inside — this is for you.

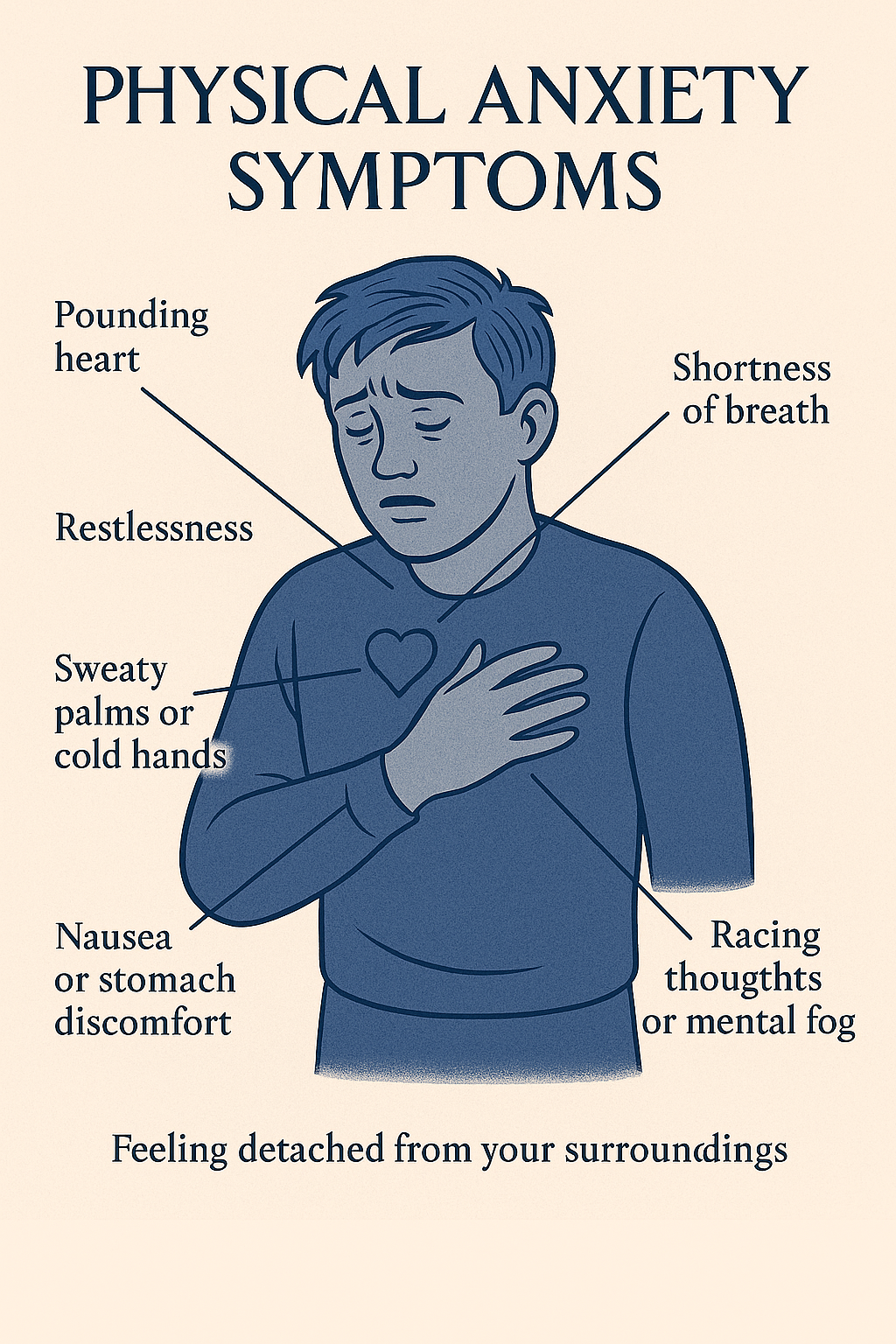

What does anxiety feel like?

It’s not always what you expect. Sometimes it’s subtle. Sometimes it’s physical. Here are some signs to watch out for:

A pounding heart, even while doing nothing

Shortness of breath, or feeling like your chest is tight

Restlessness — the inability to sit, focus, or relax

Sweaty palms or cold hands

Nausea or stomach discomfort

Racing thoughts or mental fog

Feeling detached from your surroundings (a sense of unreality)

These are symptoms of your fight-or-flight system being activated. It's your body reacting as if there’s danger — when really, you're just alone with a reviewer in your room.

It sneaks in — when you're brushing your teeth, or lying in bed, or after acing a mock bar.

You think, “This shouldn’t be happening to me.” But it does. It did.

In my case, the anxiety was sudden, sharp, and overwhelming. The kind that shortens your breath. I didn’t know where it came from — there was no specific trigger. That made it scarier.

What helped was learning to catch it. Naming it. Breathing through it. Anxiety loses power when you don’t fight it — when you observe it.

You are not your anxiety. It’s a signal, not a sentence. Let it pass through, not take over.

Mind the Mind Spiral

Bar review glorifies discipline — and rightly so. But somewhere along the way, we started worshipping the myth of the machine: the bar taker who studies 12 hours a day, eats stress for breakfast, and operates without emotion or error.

What we don’t talk about enough is the quiet unraveling beneath the surface — the tears that don’t make it to social media, the panic that doesn’t fit into planner checklists, the self-doubt that creeps in even when your scores say you’re doing well. You are not a machine. You are a whole person. And success at the bar doesn't require perfection — it requires preservation.

Before your thoughts drag you into a “what if I fail?” spiral, pause, and reframe.

Bar exam anxiety isn’t just emotional. It’s neurological. Every time you mentally rehearse worst-case scenarios, you’re building neural pathways that make those fears more dominant. That’s where neurolinguistic programming (NLP) comes in — it’s about becoming conscious of your internal scripts and changing how your brain processes fear.

Reset your mind frame

What the mind conceives, the body achieves. Your words become your reality. It is important to control the narrative early on by:

Noticing the pattern. Catch spiraling moments (e.g., “I haven’t studied enough”, “I’m not good enough”, “I’m not as good as my classmate”).

Name it without judgment. “I’m telling myself I’m behind. That’s just a story. Not a fact.”

Replace it with an anchored phrase. Create a phrase that calms and grounds you.:

“I am not in the bar exam yet. I am in a study session. And I’ve survived harder days than this.”

“This is just a mock bar. I can still improve.”

“I have been preparing for this my whole life.”

Use physical anchors. Tap your wrist or place your hand on your chest while saying the phrase. Over time, the gesture becomes a physical cue for calm.

Know When to Step Back

Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is close the book.

““You don’t want to burn out before the real test begins.”

You think you’re falling behind. But your brain isn’t a machine — it needs space to breathe, reset, and remember. De-escalating doesn’t mean giving up. It means protecting your mental clarity. Walk. Nap. Water your plants. Pause the war. You’re not wasting time. You’re making time work for you.

Atty. Edwin Sandoval once reminded me earlier during the review not to push to the point of collapse. “Rest,” he said. “You don’t want to burn out before the real test begins.”

Sing. Watch. Be Silly.

Joy is not a distraction. It’s a cognitive reset.

In the thick of bar review, I once sang karaoke in my room — just one song, out of tune, at full volume. I also watched a dumb romantic comedy I had already seen five times. For a moment, I wasn’t a bar review machine. I was just… me again.

And here’s the surprise: I didn’t forget Civil Law because of it. If anything, I remembered better the next day.

Why? Because your brain retains more when it’s not drowning in cortisol. Laughter oxygenates your mind. Music regulates your heartbeat. A 20-minute comedy break is not a waste of time: it’s recovery. So don’t feel guilty for singing your heart out to Queen or SB19, watching your favorite Netflix series, dancing on TikTok to recharge, or eating out with friends.

Even the late criminal law luminary Judge Oscar Pimentel said in our first-year class: “If you want to memorize your codals — sing the provision.”

If your joy feels like rebellion — good. You are rebelling against the lie that suffering is the only way to succeed. You are allowed to feel good, even while preparing for something hard. Learning from the readings in political law on the right to privacy, “life is not only meant to be endured, but enjoyed.”

If you were to take the bar exam once, why not enjoy it. You will never pass this way again. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Honor Your Rhythm — Sleep Included

Bar review is a marathon. The only way to last is to know your rhythm and protect it. I used productivity tools like the Pomodoro Technique, a time management method that breaks work into focused intervals, traditionally 25 minutes long, called “Pomodoros,” followed by a 5-minute break. After completing four Pomodoros, you take a longer break of 15 to 30 minutes. The method uses a timer to instill urgency, enhance focus, and reduce burnout—making it especially useful during intense study periods like bar exam prep.

Sleep isn’t a luxury. It’s a core part of cognitive function. You can’t retain what your brain didn’t get a chance to consolidate. Neuroscientists confirm REM sleep strengthens memory, and naps boost learning.

Build a routine

In my case, I built a routine comprising of:

5:00 AM — Wake and first read

7:00 AM — Breakfast and self-care

9:00 AM — Focused study

12:00 PM — Lunch

1–2 PM — Nap

2–6 PM — Review

6 PM — Dinner

8–10 PM — Final review

And by 10:00 PM — I stopped.

Naps are not laziness. They’re mini-reboots. Routine is not rigidity. It’s safety.

Protect Your Peace

Mute the chat group. Curate your feed. Stop comparing reviewer stacks or practice scores. You don’t need permission to log off.

But protecting your peace isn’t just digital — it’s spiritual and environmental too.

Build inner stillness however you can. That could mean:

Saying a short prayer before opening your codal

Taking 3 deep breaths at the start and end of each review session

Trying guided meditation or soundscapes to fall asleep

Creating a ritual: light a candle, play focus music, tidy your desk — a signal to your mind that you are safe to focus

Adjust your surroundings. If your space is noisy, wear earplugs. If it’s messy, clear just one corner. Small shifts create mental clarity.

And then, this: Stay away from people who bring chaos. Bar season is not the time to fix everyone’s life. Avoid drama. Exit the group chat with obnoxious arguments. Limit contact with those who drain you. Be kind, but firm.

Trust me. During the bar exams, your emotions will peak. And when that happens, you’ll need all the calm you’ve saved. So you need to conquer your tendency to panic, before panic conquers you.

Your peace is your fuel. Guard it like it’s part of your reviewer.

The late Dean Willard Riano also shared a lesson I’ve held close: “Be proud of who you are and what you can be.” It’s a reminder that self-trust is as essential as study, and its starts by being at peace with yourself.

Seriously Mind Your Posture

Sit up. Support your spine. Stretch your neck.

During bar review, I ignored the small body signs — until they weren’t small anymore. I wish I had paid attention.

Now in my late thirties, I feel the consequences. So I’ll say this loud: Take care of your back. Your body is carrying your dreams.

Good posture isn’t just about avoiding back pain. It’s a signal — to your brain and to the world — that you are alert, grounded, and in control.

Physically, proper posture ensures that oxygen flows more freely throughout your body. When you’re slouched or hunched over your desk for hours, your lungs compress, making breathing shallow. This reduces your energy, weakens focus, and contributes to fatigue. Sitting upright with your spine aligned improves circulation and helps keep your brain awake.

Mentally, posture can influence how you feel about yourself. According to social psychologist Amy Cuddy, who is widely known for her research on "power posing", an upright posture is linked with increased confidence and lower cortisol (stress hormone) levels. Thus, simply adjusting your body can change how your mind performs.

Cognitively, your brain responds to posture as a feedback loop. Slouching often mirrors defeat or exhaustion — and your brain picks up on that signal. Standing or sitting tall, on the other hand, reinforces a mindset of capability and readiness.

In moments of stress, like cramming for the bar or reviewing difficult cases, try this simple shift: uncross your legs, plant your feet flat on the floor, roll your shoulders back, take a deep breath and look up, not down. This posture doesn’t just feel better — it tells your body, “I’m not overwhelmed. I’m here. I’ve got this.”

Final Words

I was inspired to write this because one of the bar takers I am mentoring recently opened up about the pressure and anxiety they were feeling. It reminded me of my own story — that night I broke down with no warning, and still made it through. This post is for them, and maybe, for you too. If it helps even one person feel less alone — then it’s done its job.

You’ve probably heard it a hundred times: “Just trust the process.”

But the truth is, the process can feel terrifying. And lonely. And heavy. And sometimes, like you’re not enough.

That’s why you need to bring all of you — not just your brain, but your heart, your humor, your breath, your body. Because the bar isn’t just a test of what you know — it’s a test of who you are when no one’s watching.

And if you ever find yourself crying at 2AM, it doesn’t mean you’re weak. It means you’re already braver than most — because you showed up.

Self-mastery is part of bar mastery. The big day won’t just test your memory — it will test your mind, your rhythm, your peace.

So breathe. Stand tall. Study hard, but rest harder.

You’re not behind. You’re becoming.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed, exhausted, or isolated, this is for you—a safe space where your challenges are seen and your courage is honored. Together, we’ll walk through the darkness toward the light at the end of this difficult road. Because no one should have to face the bar alone. Let’s face it, and rise beyond it—side by side. #

Statutes of limitation for medical malpractice in the Philippines

The law sets time limits for filing court cases called statutes of limitations. Prescriptive periods also apply to medical malpractice cases. How long can someone sue for medical malpractice before it's too late?

The law sets time limits for filing court cases called statutes of limitations. Prescriptive periods also apply to medical malpractice cases. How long can someone sue for medical malpractice before it's too late?

Such quandary was answered in De Jesus v. Dr. Uyloang, Asian Hospital and Medical Center, and Dr. John Francois Ojeda (G.R. No. 234851, February 15, 2022).

The case involved a failed surgery by Drs. Uyloang and Ojeda on De Jesus for gallstones. De Jesus later had abdominal pains and bile leakage, which Dr. Uyloang said was normal.De Jesus sought a second opinion, confirming the wrong duct was clipped, leading to bile leakage. Another surgery was needed on November 19, 2010.

On November 10, 2015, after five years, De Jesus lodged a medical malpractice case against Dr. Uyloan, Asian Hospital and Medical Center and Dr. Ojeda. All of them moved for the case’s dismissal invoking that the time to file the action already prescribed.

Now, the crux of the controversy: did the action grounded on medical malpractice already prescribe?

De Jesus argued that, since the action was based on a contract between the defendant doctors and hospital, the action prescribes in six or ten years under Article 1145 and 1144 of the Civil Code, respectively.

To determine whether the De Jesus’ medical malpractice suit was barred by the statutes of limitation, the Philippine Supreme Court had to define the nature of a medical malpractice suit.

Medical Malpractice defined: contract or quasi-delict?

While jurisprudence is clear as to the requisites of establishing a physician-patient relationship, there appears to be a lacunae in what the nature of the relationship is. Does it constitute a contract?

As defined in the earlier Casumpang v. Cortejo (G.R. No. 171127, March 11, 2015), “a physician-patient relationship is created when a patient engages the services of a physician, and the latter accepts or agrees to provide care to the patient. The establishment of this relationship is consensual, and the acceptance by the physician essential.” It can be gleaned from this jurisprudential definition that the first requisite of a contract — consent — is satisfied. Does this mean that this meeting the minds between a physician and patient ourightly establishes a contractual relationship between them?

After all, contracts are born with concurrence of three : (a) consent of the contracting parties; (b) object certain which is the subject matter of the contract; and (c) cause of the obligation which is established (Art. 1318, Civil Code).

The Philippine Supreme Court held that a physician-patient relationship is not contractual. It explained:

The fact that the physician-patient relationship is consensual does not necessarily mean it is a contractual relation, in the sense in which petitioner employs this term by equating it with any other transaction involving exchange of money for services. Indeed, the medical profession is affected with public interest. Once a physician-patient relationship is established, the legal duty of care follows. The doctor accordingly becomes duty-bound to use at least the same standard of care that a reasonably competent doctor would use to treat a medical condition under similar circumstances. Breach of duty occurs when the doctor fails to comply with, or improperly performs his duties under professional standards. This determination is both factual and legal, and is specific to each individual case. If the patient, as a result of the breach of duty, is injured in body or in health, actionable malpractice is committed, entitling the patient to damages. (De Jesus v. Dr. Uyloang, et. al, supra.)

Does this pronouncement therefore foreclose any contractual relationship between a physician and a patient? Interestingly, the Philippine Supreme Court hinted that it was also possible that an action for medical malpractice can be based on contract, specifically when the plaintiff “allege[s] an express promise to provide treatment or achieve a specific result.”

Citing a textbook on American malpractice jurisprudence, “The Preparation and Trial of Medical Malpractice Cases[,]” the Philippine Supreme Court expounded that:

Absent an express contract, a physician does not impliedly warrant the success of his or her treatment but only that he or she will adhere to the applicable standard of care. Thus, there is no cause of action for breach of implied contract or implied warranty arising from an alleged failure to provide adequate medical treatment. This allegation clearly sounds in tort, not in contract; therefore, the plaintiff's remedy is an action for malpractice, not breach of contract. A breach of contract complaint fails to state a cause of action if there is no allegation of any express promise to cure or to achieve a specific result. A physician's statements of opinion regarding the likely result of a medical procedure are insufficient to impose contractual liability, even if they ultimately prove incorrect. (Shandell and Smith, 2006)

Following this logic, we can draw this conclusion: absent any specific promise to cure or achieve a definite result, no contractual relationship between them arises notwithstanding the physician’s acceptance of the patient’s engagement. Supporting this conclusion are rulings of the Philippine Supreme Court in earlier cases which recognizes that physicians are not insurers of life (Ramos v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 124354, December 29, 1999) and good result of treatment (Lucas v. Dr. Tuaño, G.R. No. 178763, April 21, 2009).

Verily, that physicians cannot and do not guarantee that a patient will be cured is already well-entrenched in Philippine jurisprudence. Seemingly, this jurisprudential trend will not favor award of damages based on contract liability theory in medical malpractice suits, notwithstanding the the settled doctrine that liability for quasi-delict may co-exist in the presence of contractual relations.

The inescapable conclusion then is the period of prescription for quasi-delict applies in medical malpractice cases.

Nature of medical malpractice cases

American legal system classifies medical malpractice or medical negligence as a form of “tort.” The Philippines, however, does not have “tort” imbedded in its legal system. Instead, the Civil Code of the Philippines provides for a system of quasi-delict. Chief Justice Alexander Gesmundo speaking in De Jesus eruditely explains:

For lack of a specific law geared towards the type of negligence committed by members of the medical profession in this jurisdiction, such claim for damages is almost always anchored on the alleged violation of Art. 2176 of the Civil Code, which states that:

ART. 2176. Whoever by act or omission causes damage to another, there being fault or negligence, is obliged to pay for the damage done. Such fault or negligence, if there is no pre-existing contractual relation between the parties, is called a quasi-delict and is governed by the provisions of this Chapter.

Medical malpractice is a particular form of negligence which consists in the failure of a physician or surgeon to apply to his practice of medicine that degree of care and skill which is ordinarily employed by the profession generally, under similar conditions, and in like surrounding circumstances. In order to successfully pursue such a claim, a patient must prove that the physician or surgeon either failed to do something which a reasonably prudent physician or surgeon would have done, or that he or she did something that a reasonably prudent physician or surgeon would not have done, and that the failure or action caused injury to the patient. There are thus four elements involved in medical negligence cases, namely: duty, breach, injury, and proximate causation. (De Jesus v. Dr. Uyloang, et. al, supra.)

While the contract theory of medical malpractice cases was debunked, it does not mean that victim of medical malpractice or medical negligence are without recourse. The Philippine Supreme Court’s pronouncement in De Jesus only indicates that medical malpractice victims may vindicate their rights by filing an action for damages based on quasi-delict. Parenthetically, they can also file a case for criminal negligence under Article 365 of the Revised Penal Code (on Quasi-Crimes).

Drawing lessons from the De Jesus case, victims of medical malpractice should ever be mindful of the prescriptive period in filing the suit within the prescriptive period. Simply put, as in any case, time is of the essence.

Revisiting statute of limitations in civil cases

Generally, statutes of limitation are provided for in specific laws. In so far as civil cases are concerned, absent specific prescriptive period under special law, the Civil Code applies. Determinative in the case of De Jesus are Articles 1144, 1145 and 1146 of the Civil Code, to wit:

ARTICLE 1144. The following actions must be brought within ten years from the time the right of action accrues:

(1) Upon a written contract;

(2) Upon an obligation created by law;

(3) Upon a judgment.

ARTICLE 1145. The following actions must be commenced within six years:

(1) Upon an oral contract;

(2) Upon a quasi-contract.

ARTICLE 1146. The following actions must be instituted within four years:(1) Upon an injury to the rights of the plaintiff;

(2) Upon a quasi-delict;

However, when the action arises from or out of any act, activity, or conduct of any public officer involving the exercise of powers or authority arising from Martial Law including the arrest, detention and/or trial of the plaintiff, the same must be brought within one (1) year.

Falling under the broad concept of quasi-delict, medical malpractice cases prescribe within four-years from the commission of such wrongful act or omission. Clearly, De Jesus’ medical malpractice suit came one year too late. It took him five years to pursue his claim against Drs. Uyloang and Ojeda, as well as Asian Hospital and Medical Center. As to why he waited for time to slip away, we could only surmise. This curious case serves as a reminder and a caveat what tons of law books have been saying all along: “the law helps the vigilant but not those who sleep on their rights.” Vigilantibus, sed non dormientibus jura subverniunt.

Filipino nurses: Too many, but never enough

Healthcare workers in government, including nurses, cheered when it was announced on July 9, 2024 that the Department of Health will release around P27.4 billion health emergency allowance for health workers who served during the height of the COVID-19. Will this be enough to keep them from fleeing the country to search for greener pastures? Only time will tell.

Healthcare workers in government, including nurses, cheered on when it was announced on July 9, 2024 that the Department of Health will release around P27.4 billion health emergency allowance for health workers who served during the height of the COVID-19. Will this be enough to keep them from fleeing the country to search for greener pastures? Only time will tell.

For a country that prides itself as one of the world’s largest producers of nurses, the Philippines is faced with the paradox of having a surplus of nurses yet still never enough to sustain its much-needed army of nurses during the battle against COVID-19. Overseas migration was not the only factor affecting deficient supply of nurses in the Philippines. The lack of stable jobs and dismal wages also factored in. (Ortiga & Rivero, 2019). Inadequate state funding to hire more nurses worsened this existing crisis in nursing supply. (Perrin, Hagopian, Sales, & Huang, 2007)

The International Centre on Nurse Migration reports close to six million shortfalls of nurses even prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Buchanan, Catton & Shaffer, 2022) retaining nurses and maintaining adequate supply of nursing workforce challenged many countries. It compelled nations to implement drastic and "emergency" policy actions to keep a sufficient regiment of nurses. The Philippines is no exception.

In 2020, the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) through Governing Board Resolution No. 9, 2020 banned the deployment of health workers abroad. The deployment ban was due to a reported shortage of 290,000 health workers in the country. (Governing Board Resolution No. 9, 2020) The shortfall in health workers was aggravated by an average annual migration of 13,000 health care professionals that aggravated the deficiency in national supply of health human resource, majority of whom are nurses. (Ibid.)

After a huge public backlash, the POEA Governing Board issued Governing Board Resolution No. 17 which temporarily lifted the ban but imposed an annual overseas deployment cap of 5,000 new hire healthcare workers starting January 1, 2021. (Governing Board Resolution No. 17, 2020)

During the pandemic, nurses were seen as “heroes” of the war against COVID-19. However, Rowalt Alibudbud (2022) argues that it’s not enough to honor nurses during the Covid-19 crisis. (Alibubud, 2022) Honor sans just proper wages, adequate staffing and livable conditions will not sustain the Philippines’ Covid-19 response. He observed, “hospitals in the country began downsizing operations, not because of lack of facilities, but rather because of lack of health care workers.” (Alibubud, 2022)

Agence France-Presse (2021) reports the alarming plight of nurses experiencing burn out in the midst of the unprecedented rise COVID-19 cases in 2021, which ultimately led most of them to quit nursing. The article notes that the nursing service in most hospitals were already “dangerously understaffed even before the pandemic.” (Agence France-Presse, 2021)

Filipino Nurses United President, Maristela Abenojar, attributes such “chronic understaffing” to inadequate salaries of Filipino nurses. On paper, an entry-level nurse in a private hospital is entitled to earn Salary Grade 15, which is roughly Php 33,575.00 (US$ 670.00) per month. However, according to Abenojar, in reality, there are still nurses in the public hospitals who are employed on short-term contracts, earning Php 22,000.00 per month with no benefits such as statutorily-mandated hazard pay. (Agence France-Presse, 2021)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, overseas recruitment of nurse became widespread and aggressive. While reforms in the nursing policies are seen in increments, the circumstances beg the question whether our government has done enough to retain our pool of nurses and instill in them a sense of nationalism that would make them stay.

The twenty year saga for nurse’s equitable wages

We cannot blame Filipino nurses if they have their a strong desire to migrate. Afterall, they have been fighting for 20 years for government to hear their call to implement the statutory wage under Republic Act (RA) No. 9173.

In order to enhance the general welfare, commitment to service and professionalism of nurses, the minimum base pay of nurses working in the public health institutions shall not be lower than salary grade (SG) 15 prescribed under Republic Act No. 6758, otherwise known as the “Compensation and Classification Act of 1989”: Provided, That for nurses working in local government units, adjustments to their salaries shall be in accordance with Section 10 of the said law.

This provision on minimum base pay of entry level nurse in public health institutions incorporated the prevailing Compensation and Classification Act of 1989 or RA 6758. Under Section 9,in relation to Section 7 of RA 6758, the minimum base pay of nurses was classified as SG 10 or Php 3,102.00 (1st Step) to Php 3,325.00 (8th Step) prior to the effectivity of RA 9173.

Section 32 of RA 9173, thus, upgraded the salary grade for entry level nurses in public health institutions for SG 10 to SG 15 (Php 4,418.00 to Php 4,737). On 28 July 2008, the Congress approved Joint Resolution (JR)No. 4 (Salary Standardization Law III) authorizing the President to Modify the Compensation and Position Classification System of Civilian Personnel and Base Pay Schedule of Military and Uniformed Personnel in the Government, and For Other Purposes.” Under Section Item 3 (a) of JR No. 4, SG 15 was equivalent to Php 24,887 to Php 26,868. However, JR No. 4 expressly repealed RA 9173.

On 17 June 2009, President Macapagal-Arroyo approved JR No. 4 and issued Executive Order (EO) No. 811 implementing JR No. 4. Section 6 of Executive Order No. 811, downgraded the SG assignment for entry level nurses from SG 15 as provided under Section 32 of RA 9173 to SG 11 (Php 18,549.00 to Php 19,887.00).

On 8 October 2019, the Supreme Court step its foot against the downgrading of the pay grade of entry level nurses in public health institutions from SG 15 to SG 11 through a mere Joint Resolution and Executive Order implementing the same in the case of Ang Nars Party-List v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 215746, October 8, 2019.

In this case, the Supreme Court clarified that a JR is not a law or a statute, thus, it was held that it cannot repeal the provision of RA 9173:

Under Section 26 (2), Article VI of the 1987 Constitution, only a bill can be enacted into law after following certain requirements expressly prescribed under the Constitution. A joint resolution is not a bill, and its passage does not enact the joint resolution into a law even if it follows the requirements expressly prescribed in the Constitution for enacting a bill into a law.

xxx xxx xxx

A bill is, of course, vastly different form a joint resolution. First, a bill to be approved by Congress must pass three (3) readings on separate days. The can be no deviation from this requirement, unless the President certifies that the bull as urgent. In contrast, Congress can approve a joint resolution in one, two or three readings, on the same day or on separate days, depending on the rules of procedure that the Senate or the House may, at their sole discretion, adopt.