Search articles

Informed Consent: A Surgeon’s Strongest Legal Tool Against Malpractice

A scalpel might save a life. But a conversation between a doctor and a patient—clear, candid, and properly documented—saves a medical practitioner’s life or career. In the sterile world of operating rooms and legal briefs, few things cut as sharply as informed consent.

It began, as these stories often do, with a consent form and a signature.

A man with an aortic aneurysm was scheduled for a stenting procedure. His surgeon walked him through the risks and his options. He agreed and signed the consent forms. Stenting proved unsuccessful. Days later, he died. The family mourned and, thereafter, lodged a malpractice suit.

This is a short-hand retelling of the case of Que v. Philippine Heart Center, G.R. No. 268308, April 02, 2025. A legal battle that reached its final verdict 25 years after the patient’s death.

The crux of the case lay in a fundamental, but often overlooked, concept in legal medicine: informed consent. In Que, the Philippine Supreme Court reaffirmed one of the most powerful legal doctrines in medicine: informed consent, when rightfully obtained, is sharper than any scalpel.

In a nutshell, the Supreme Court cleared the physician because he fulfilled his duty to explain, inform, and document consent. In the words of the Supreme Court:

“The facts would show that Dr. Aventura informed the Que family, most especially Quintin, of the material risks inherent in the stenting procedure, and that includes death.”

The records show that the patient signed the Consent for Endovascular Stenting and the Consent to Operation, Administration of Anesthesia, and the Rendering of Other Medical Services. His signature appeared in these documents, and this was never questioned.

When tragedy strikes, the conversation between a physician and a patient isn’t just a formality—it becomes evidence, a lifeline in a murky sea of legal scrutiny. The doctrine is not about absolving doctors of blame; it’s about ensuring clarity, mutual understanding, and trust between the caregiver and the cared for.

By no means does the case state that signing a consent is a carte blanche excuse for negligence or malpractice. Malpractice needs to be proven with hard evidence unless it falls under the doctrine of res ipsa loquitur.

Lessons from the courtroom to the operating room

In an overstretched healthcare system, where one physician may be responsible for dozens of patients on any given shift, the ritual of informed consent often collapses into routine. Doctors and nurses, pressed for time, may move robotically through the process: handing over forms that are signed, but not truly understood.

Yes, the paperwork is there. But the information? Often absent.

This is the uneasy paradox at the heart of Philippine hospitals: consent is technically obtained, but substantively hollow. In too many cases, the signature becomes a substitute for the conversation. I have seen this firsthand.

What Que forces us to confront is a powerful truth: informed consent is not merely about protecting the physician or the institution—it’s about empowering the patient. The importance of informed consent resonates as a beacon of communication, one rooted not merely in paperwork but in the human connection that defines caring at its core.

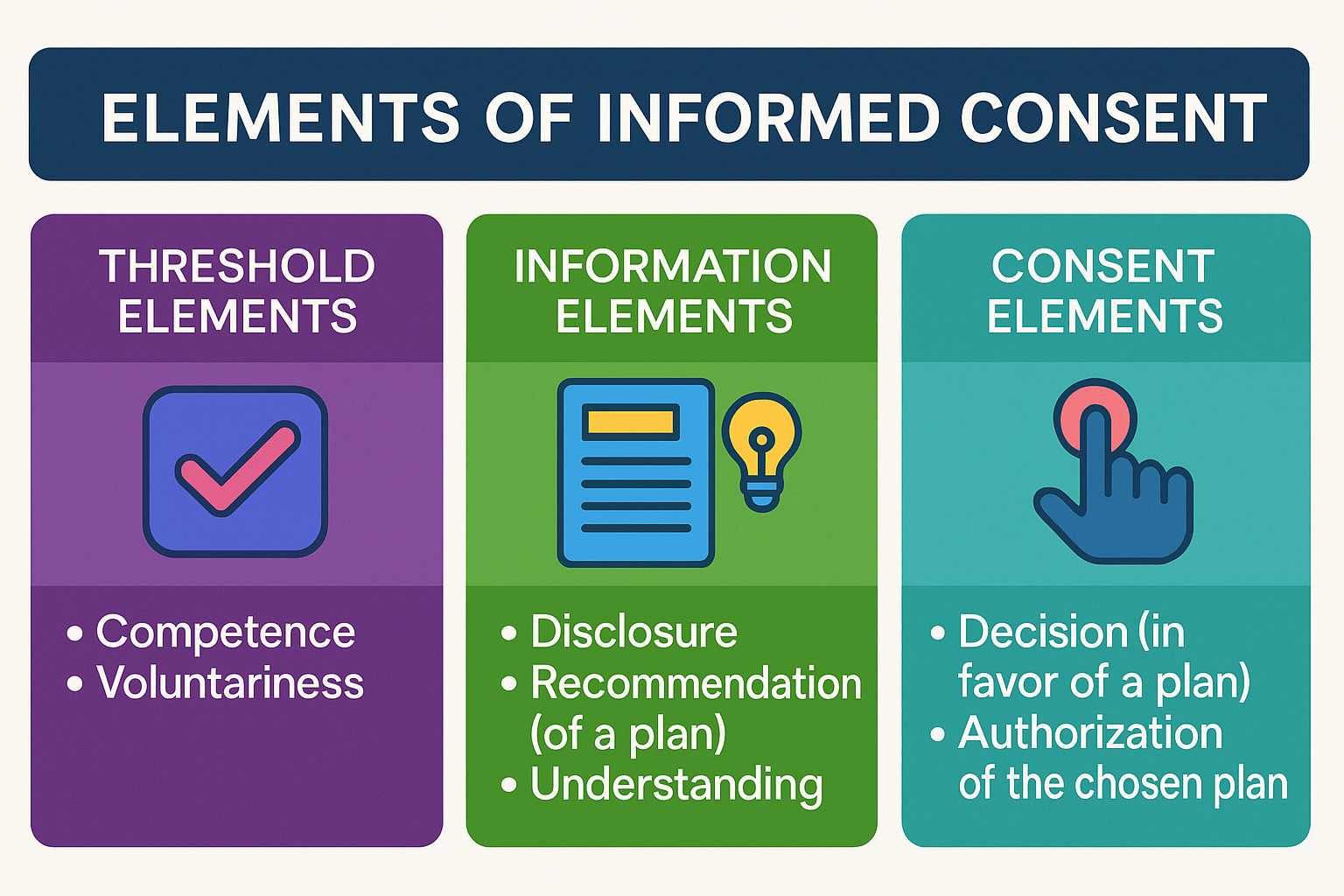

As a lecturer on nursing ethics and legal medicine, I often emphasized a framework first outlined by bioethicists Beauchamp and Childress (2013). This model dissects consent into three pivotal stages: threshold, information, and consent.

This framework is based on the model proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, as cited by the Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University. (Source: Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Meaning and Elements of Informed Consent. Berman Institute of Bioethics, Johns Hopkins University. https://bioethics.jhu.edu)

Elements of Informed Consent

Threshold elements serve as the foundational preconditions for informed consent, ensuring that the patient is both capable of making decisions and free from undue influence. A medical practitioner should ascertain the patient’s competence and the voluntariness of decision-making.

Competence refers to the patient’s ability to understand medical information, evaluate options, and make informed decisions. Competence is not merely a legal concept but also a practical one, requiring healthcare providers to evaluate whether the patient has the cognitive and emotional capacity to grasp the implications of their choices.

Voluntariness, on the other hand, underscores the importance of a patient's decision being made free from coercion, manipulation, or external pressures. Whether the influence comes from family members, medical staff, or societal expectations, voluntariness ensures that the patient’s autonomy and personal agency are respected in the decision-making process.

Information elements are crucial to the process of informed consent, ensuring that patients are provided with sufficient details to make a knowledgeable decision regarding their medical care. They include:

Disclosure or the sharing of all material information that a patient needs to understand the medical procedure, including its purpose, benefits, risks, and potential alternatives.

Recommendation that goes a step beyond disclosure by providing the physician's professional opinion on the best course of action. While laying out all the possible scenarios, a healthcare provider must guide the patient toward an informed choice by interpreting the medical data and suggesting a preferred plan.

Understanding -- the final, pivotal component of the information elements– that ensures that the patient not only hears the information but also comprehends it fully. This stage might involve confirming the patient's grasp of the disclosed risks, benefits, and alternatives by engaging them in dialogue, answering their questions, and clarifying any uncertainties. The focus here is to ensure that the patient is genuinely aware and capable of making an informed decision.

Consent elements are essential to completing the process of informed consent and represent the final stage of patient decision-making. They comprise two critical components:

A decision that involves the patient's active choice in favor of a proposed plan or procedure. It is the moment in which the patient exercises their autonomy to determine what they believe to be the best course of action for their health.

Authorization, which marks the formal agreement to proceed with the chosen plan, serves as the confirmation that the patient has willingly provided consent, free from coercion or undue influence. It often involves a signed consent form.

Together, these elements affirm the patient's role as an active participant in their healthcare journey, underscoring the importance of respect, transparency, and ethical practice in medical decision-making.

While the importance of informed consent had been highlighted in earlier precedents, Que serves as a definitive example of the critical importance of informed consent, underscoring its role as a cornerstone of legally sound medical practice.

When tragedy strikes, as it did in this case, consent becomes the anchor that steadies a physician in the storm of loss and litigation, while serving as a testament to the patient’s agency in their own care.

This doctrine, affirmed by the Philippine Supreme Court, should echo in every hospital corridor, every operating room, and every medical school lecture. It demands a rethinking of how we view conversations between doctors and patients—not as perfunctory exchanges, but as critical lifelines, ensuring that medicine remains rooted in the very humanity it seeks to preserve.

No one expects doctors to be insurers of lives. But they are expected to ensure that patients understand the risks in the course of treatment. That means, doctors must exert efforts to:

Speak plainly, not just professionally.

Disclose the full range of risks, including death or disability.

Respect the silence between questions. Listen to what the patient is not saying.

Record the consent not just with ink, but with intention.

The law won’t punish honest medicine. But it does demand transparent communication.

Where is the nurse in all of this?

As a former professor of legal aspects in nursing, I often posed a critical question to my students during case discussions on medical malpractice: where is the nurse in all of this?

It’s a common misconception that nurses secure consent. Legally, that’s the physician’s role. But nurses play a quiet, indispensable one: they advocate. The nursing duty is subtle, but powerful:

Observe whether the patient appears to fully understand the procedure.

Notice verbal and non-verbal cues—hesitation, confusion, fear.

Record any clarifications the patient requests.

Raise concerns to the attending physician before the procedure proceeds.

In healthcare, nurses hold a role less visible but no less vital: ensuring patients are not adrift in uncertainty. While they do not explain the intricacies of medical procedures—that responsibility rests firmly with physicians—they serve as the guardians of comprehension and clarity. Their duty extends beyond care to meticulous documentation, as underscored by the Nursing Code of Ethics for Filipino Nurses: “Accurate documentation of actions and outcomes of delivered care is the hallmark of nursing accountability.” [Article III, Section 6 (3), Board of Nursing Resolution No. 220, s. 2004]. Through this quiet vigilance, nurses stand as the system’s conscience, ensuring every patient’s dignity remains intact.

“Accurate documentation of actions and outcomes of delivered care is the hallmark of nursing accountability.”

What they witness in the hallway or at the bedside may later shape a courtroom’s view of what happened. Nurses aren’t passive bystanders. They are the system’s pulse-check. And when they speak up, they often speak for those who can’t.

Final cut: why consent still matters

Informed consent is not just a line on a checklist. It’s a promise—a small but vital act of dignity in a system that often forgets how human medicine truly is.

When done right, it empowers the patient. It protects the professional. It restores faith in a process that too often collapses into litigation and blame.

The sharpest tool in healthcare isn’t a scalpel. It’s the truth, told clearly, before the first cut.

🙏 Thanks for Reading

If this piece made you pause—or stirred a new question—then it's done its job.

Got something to say? Add your voice below. Got a topic worth unpacking? Tell me.

Subscribe to Seen and Heard for legal insights, reflective storytelling, and honest conversations at the intersection of health and law.

Statutes of limitation for medical malpractice in the Philippines

The law sets time limits for filing court cases called statutes of limitations. Prescriptive periods also apply to medical malpractice cases. How long can someone sue for medical malpractice before it's too late?

The law sets time limits for filing court cases called statutes of limitations. Prescriptive periods also apply to medical malpractice cases. How long can someone sue for medical malpractice before it's too late?

Such quandary was answered in De Jesus v. Dr. Uyloang, Asian Hospital and Medical Center, and Dr. John Francois Ojeda (G.R. No. 234851, February 15, 2022).

The case involved a failed surgery by Drs. Uyloang and Ojeda on De Jesus for gallstones. De Jesus later had abdominal pains and bile leakage, which Dr. Uyloang said was normal.De Jesus sought a second opinion, confirming the wrong duct was clipped, leading to bile leakage. Another surgery was needed on November 19, 2010.

On November 10, 2015, after five years, De Jesus lodged a medical malpractice case against Dr. Uyloan, Asian Hospital and Medical Center and Dr. Ojeda. All of them moved for the case’s dismissal invoking that the time to file the action already prescribed.

Now, the crux of the controversy: did the action grounded on medical malpractice already prescribe?

De Jesus argued that, since the action was based on a contract between the defendant doctors and hospital, the action prescribes in six or ten years under Article 1145 and 1144 of the Civil Code, respectively.

To determine whether the De Jesus’ medical malpractice suit was barred by the statutes of limitation, the Philippine Supreme Court had to define the nature of a medical malpractice suit.

Medical Malpractice defined: contract or quasi-delict?

While jurisprudence is clear as to the requisites of establishing a physician-patient relationship, there appears to be a lacunae in what the nature of the relationship is. Does it constitute a contract?

As defined in the earlier Casumpang v. Cortejo (G.R. No. 171127, March 11, 2015), “a physician-patient relationship is created when a patient engages the services of a physician, and the latter accepts or agrees to provide care to the patient. The establishment of this relationship is consensual, and the acceptance by the physician essential.” It can be gleaned from this jurisprudential definition that the first requisite of a contract — consent — is satisfied. Does this mean that this meeting the minds between a physician and patient ourightly establishes a contractual relationship between them?

After all, contracts are born with concurrence of three : (a) consent of the contracting parties; (b) object certain which is the subject matter of the contract; and (c) cause of the obligation which is established (Art. 1318, Civil Code).

The Philippine Supreme Court held that a physician-patient relationship is not contractual. It explained:

The fact that the physician-patient relationship is consensual does not necessarily mean it is a contractual relation, in the sense in which petitioner employs this term by equating it with any other transaction involving exchange of money for services. Indeed, the medical profession is affected with public interest. Once a physician-patient relationship is established, the legal duty of care follows. The doctor accordingly becomes duty-bound to use at least the same standard of care that a reasonably competent doctor would use to treat a medical condition under similar circumstances. Breach of duty occurs when the doctor fails to comply with, or improperly performs his duties under professional standards. This determination is both factual and legal, and is specific to each individual case. If the patient, as a result of the breach of duty, is injured in body or in health, actionable malpractice is committed, entitling the patient to damages. (De Jesus v. Dr. Uyloang, et. al, supra.)

Does this pronouncement therefore foreclose any contractual relationship between a physician and a patient? Interestingly, the Philippine Supreme Court hinted that it was also possible that an action for medical malpractice can be based on contract, specifically when the plaintiff “allege[s] an express promise to provide treatment or achieve a specific result.”

Citing a textbook on American malpractice jurisprudence, “The Preparation and Trial of Medical Malpractice Cases[,]” the Philippine Supreme Court expounded that:

Absent an express contract, a physician does not impliedly warrant the success of his or her treatment but only that he or she will adhere to the applicable standard of care. Thus, there is no cause of action for breach of implied contract or implied warranty arising from an alleged failure to provide adequate medical treatment. This allegation clearly sounds in tort, not in contract; therefore, the plaintiff's remedy is an action for malpractice, not breach of contract. A breach of contract complaint fails to state a cause of action if there is no allegation of any express promise to cure or to achieve a specific result. A physician's statements of opinion regarding the likely result of a medical procedure are insufficient to impose contractual liability, even if they ultimately prove incorrect. (Shandell and Smith, 2006)

Following this logic, we can draw this conclusion: absent any specific promise to cure or achieve a definite result, no contractual relationship between them arises notwithstanding the physician’s acceptance of the patient’s engagement. Supporting this conclusion are rulings of the Philippine Supreme Court in earlier cases which recognizes that physicians are not insurers of life (Ramos v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 124354, December 29, 1999) and good result of treatment (Lucas v. Dr. Tuaño, G.R. No. 178763, April 21, 2009).

Verily, that physicians cannot and do not guarantee that a patient will be cured is already well-entrenched in Philippine jurisprudence. Seemingly, this jurisprudential trend will not favor award of damages based on contract liability theory in medical malpractice suits, notwithstanding the the settled doctrine that liability for quasi-delict may co-exist in the presence of contractual relations.

The inescapable conclusion then is the period of prescription for quasi-delict applies in medical malpractice cases.

Nature of medical malpractice cases

American legal system classifies medical malpractice or medical negligence as a form of “tort.” The Philippines, however, does not have “tort” imbedded in its legal system. Instead, the Civil Code of the Philippines provides for a system of quasi-delict. Chief Justice Alexander Gesmundo speaking in De Jesus eruditely explains:

For lack of a specific law geared towards the type of negligence committed by members of the medical profession in this jurisdiction, such claim for damages is almost always anchored on the alleged violation of Art. 2176 of the Civil Code, which states that:

ART. 2176. Whoever by act or omission causes damage to another, there being fault or negligence, is obliged to pay for the damage done. Such fault or negligence, if there is no pre-existing contractual relation between the parties, is called a quasi-delict and is governed by the provisions of this Chapter.

Medical malpractice is a particular form of negligence which consists in the failure of a physician or surgeon to apply to his practice of medicine that degree of care and skill which is ordinarily employed by the profession generally, under similar conditions, and in like surrounding circumstances. In order to successfully pursue such a claim, a patient must prove that the physician or surgeon either failed to do something which a reasonably prudent physician or surgeon would have done, or that he or she did something that a reasonably prudent physician or surgeon would not have done, and that the failure or action caused injury to the patient. There are thus four elements involved in medical negligence cases, namely: duty, breach, injury, and proximate causation. (De Jesus v. Dr. Uyloang, et. al, supra.)

While the contract theory of medical malpractice cases was debunked, it does not mean that victim of medical malpractice or medical negligence are without recourse. The Philippine Supreme Court’s pronouncement in De Jesus only indicates that medical malpractice victims may vindicate their rights by filing an action for damages based on quasi-delict. Parenthetically, they can also file a case for criminal negligence under Article 365 of the Revised Penal Code (on Quasi-Crimes).

Drawing lessons from the De Jesus case, victims of medical malpractice should ever be mindful of the prescriptive period in filing the suit within the prescriptive period. Simply put, as in any case, time is of the essence.

Revisiting statute of limitations in civil cases

Generally, statutes of limitation are provided for in specific laws. In so far as civil cases are concerned, absent specific prescriptive period under special law, the Civil Code applies. Determinative in the case of De Jesus are Articles 1144, 1145 and 1146 of the Civil Code, to wit:

ARTICLE 1144. The following actions must be brought within ten years from the time the right of action accrues:

(1) Upon a written contract;

(2) Upon an obligation created by law;

(3) Upon a judgment.

ARTICLE 1145. The following actions must be commenced within six years:

(1) Upon an oral contract;

(2) Upon a quasi-contract.

ARTICLE 1146. The following actions must be instituted within four years:(1) Upon an injury to the rights of the plaintiff;

(2) Upon a quasi-delict;

However, when the action arises from or out of any act, activity, or conduct of any public officer involving the exercise of powers or authority arising from Martial Law including the arrest, detention and/or trial of the plaintiff, the same must be brought within one (1) year.

Falling under the broad concept of quasi-delict, medical malpractice cases prescribe within four-years from the commission of such wrongful act or omission. Clearly, De Jesus’ medical malpractice suit came one year too late. It took him five years to pursue his claim against Drs. Uyloang and Ojeda, as well as Asian Hospital and Medical Center. As to why he waited for time to slip away, we could only surmise. This curious case serves as a reminder and a caveat what tons of law books have been saying all along: “the law helps the vigilant but not those who sleep on their rights.” Vigilantibus, sed non dormientibus jura subverniunt.